It was 2:45am when I was woken to go on deck for the hardest watch of the day: 3am-6am. That brief moment between waking and dressing was important to know what gear to wear. Quiet, easy motion indicated warm clothes and wooly hat. The violent lurches of the boat and a loud rush of water overhead meant I’d be clambering into all the protective gear I could find: drysuit, harness, lifejacket and sea boots.

This was near the Grand Banks, an area of shallow water off Newfoundland that were rich fishing grounds but dangerous in a storm. It was during the last part of a transatlantic sailing race in September 2000. We had crossed the chilly Labrador current and were closing in on Boston having started in Southampton a couple of weeks earlier.

When had been tracking the weather forecasts showing a storm would pass as we planned to cross the Grand Banks. We evaluated the options and decided sailing South to remain in deeper waters was safest. We prepared the boat and ourselves for a difficult 24 hours and raced on. We were all tense, but we were ready.

These days the challenges I face are in the world of health IT. As I work in the Acute Delivery function of the Office of the CIO, I spend my time with managers and leaders in health figuring out how to travel the journey to more effective, efficient and safe services. These decisions are rarely straightforward, involve incomplete information, unforeseen consequences and significant uncertainties; much like the challenges I faced with my crew-mates crossing the Atlantic.

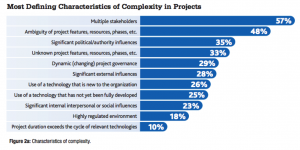

The Project Management Institute publication “Navigating Complexity” describes what constitutes a complex project:

These characteristics are present in many of the projects I’m involved in, day-in, day-out. Introducing technology to support patients and health professionals is usually broadly welcomed. But when the simplicity of pen and paper is replaced by the complications of structured data capture and formal workflows there are many challenges to overcome. Dr. Tony Shannon, a health informatics leader with Ripple, has shared many insights from complexity theory and how they help understand health systems.

As I work with hospitals and hospital groups to plan their IT investments into the future, there are many additional characteristics of complexity in play. Decision-making with imperfect information, ambiguity, and developments in the policy environment is decision-making under pressure. Nonetheless, decisions must be made.

The process we follow uses these approaches:

- Clarity on where you intend to be: infrastructure, applications and integrations;

- Understanding where you are in terms of systems, capabilities and skills;

- Chart the best course possible from where you are, start the journey, and expect it to change as you go.

Nationally, a lot of effort has gone into developing a clear, coherent and costed view of an Irish Health system enabled by the Electronic Health Record. Part of being clear about where a hospital group intends to use IT, is to be clear how the EHR will enable their part of the health system.

Equally important is knowing the current infrastructure, systems and capacity of the hospital group. It’s more than just technology. It’s about understanding how the people involved in health IT can further contribute to health transformation.

The third part of the approach is to chart a course towards the desired future, identifying intermediate waypoints and milestones along the way. This involves making difficult choices about how to apply precious resources and skills to start and complete projects that will bring the organisation towards the vision. Small gains build to big wins for our health professionals, for our service users and for our communities.

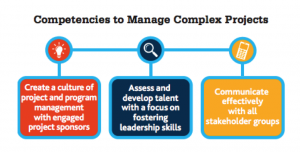

The PMI guidance is valuable and describes the competencies required to manage complexity.

There is no one formula that assures success. Choices have to be made with incomplete information, with an uncertain landscape and unknown risks. Establishing the way forward requires collaboration between health IT experts, clinician leaders and service management.

When we skirted the Grand Banks in September 2000 we were making the best decisions possible with imperfect information. There was a storm we couldn’t avoid, but we planned ahead and we were ready for it; we battened down the hatches, we ate early, we shortened sail, we kept each other safe and we adapted to the conditions that came. With a mixture of exhaustion and relief we emerged out of that storm unscathed.

Thankfully there are few days in the office as dramatic as a storm on the Grand Banks. But the challenges we deal with on ordinary days are just as important. They require skill, perseverance, and good judgement. Patience, teamwork and communication are essential. And always with an eye on the forecast and horizon…